PechaKucha (PK) is a presentation method that has been around for a little over a decade, and it has been making steady inroads into classrooms from the K–12 to graduate levels, and across the curriculum. The concept and design are simple. But PK can be modified and structured in various ways to encourage particular outcomes. Because visual and graphic creativity are prominent components of the PK method, it can be an effective learning and teaching tool for almost any topic, especially so for Asian studies. The process of selecting and incorporating visual images and cues in the presentation augments the delivery and understanding of culturally and linguistically unfamiliar concepts that are always a part of any course on Asia. For example, concepts such as guangxi in Chinese society or nemawashi in Japan have complex meanings that do not map entirely onto Western translations such as “connections” or “groundwork.” Visual aids selected by students can be a valuable starting point for both checking their “gut-level” understanding, as well as provoking discussion about their definitions, roles, and effects.

PK encourages students to grab images from the web to incorporate into their presentations and to consider how these images convey their information in meaningful and relevant ways. In addition, PK can help eliminate the worst elements and tendencies of student presentations, such as poor organization, preparation, and lengthiness. It is useful both for streamlining and adding necessary structure to class presentations. The PK structure also makes it easier to construct fair and meaningful grading rubrics, which can be much more difficult with unstructured presentations. Finally, the preparation of PK presentations can be very useful for helping students organize research papers. This teaching article covers the basics of PK and offers suggestions for how to incorporate it into the classroom.

PK Origins

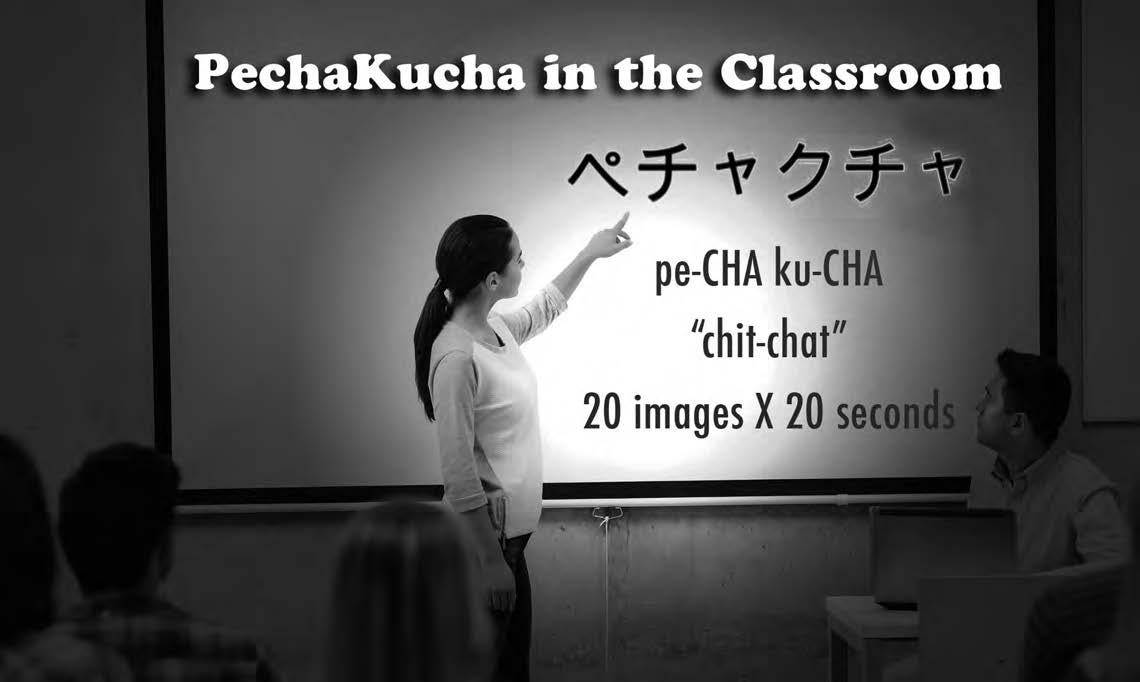

PechaKucha 20×20, its official title, is a presentation method developed in 2003 by two Tokyo architects, Astrid Klein and Mark Dytham, according to its website (www.pecha-kucha.org). “Pecha-kucha” is onomatopoeic Japanese meaning “chit-chat.” The method was developed as a way for designers to network and present their ideas to each other, but it soon took off as a socializing event. In Tokyo and now in many metropolitan areas, PK events are widely advertised, with clubs, theaters, universities, and private homes serving as venues that host PK “salons” or parties with various themes.

PK Format and Settings

Strictly speaking, the PK 20×20 format is quite straightforward: Presenters must prepare an electronic slideshow consisting of twenty slides that each appear for twenty seconds, for a total time of six minutes, forty seconds. The art (and the work) lies in communicating one’s ideas within this strict format, which imposes discipline in terms of the amount of material presented, as well as encourages clarity and organization.

In order to stay within the PK parameters, presenters should set their slideshows to automatically transition slides every twenty seconds. Because Microsoft PowerPoint and Apple Keynote are the two most commonly used slideshow programs, I will give the settings for them. On PowerPoint 2008 or 2011 for Mac OS X, go to the dropdown “Slideshow” menu and select “Transitions.” This will bring up a bar at the top of the slideshow and an “Options” button in the upper left-hand corner. Press the button, and under the “Advance Slide” category, choose “Automatically after _ seconds.” Enter twenty seconds. In the Windows version, go to the “Slideshow” menu and look for “Slide Transition.” Choose the “Automatically” option there, and enter twenty seconds. For Keynote, choose “Slide Inspector” within the Inspector; choose “Transition” and change “Start Transition” to “Automatically,” entering twenty seconds in the box.

Students have noted that while the preparation for PK is fun and the selection of images is especially enjoyable, the construction of a presentation is hard work, especially as it reveals to them the flaws or weaknesses in their arguments, or lack of organization and clarity.

Classroom Use

PK’s structured format means that students must rely more on content and information rather than design, though as I explain below, design consideration is an important aspect of communicating content.

The first step is to properly set student expectations about the presentations. A grading rubric sheet that sets out the assessment paramaters, handed out in advance of the assignment, is helpful for both students and the instructor for grading these presentations. For example, expectations on content might include requirements that:

- The research question/hypothesis/claim is clearly stated in one slide.

- That information is properly cited.

- That arguments supporting or refuting the hypothesis or claim are clearly presented.

- Data or examples are presented.

- Alternative explanations are proffered.

- The conclusion(s) is clearly stated in at least one slide.

On stylistic matters, expectations are that:

- The presenter speaks clearly with good modulation and uses professional and clear language.

- Slides do not show more information than can be processed in twenty seconds.

- Slides are well-organized with a logical and smooth flow.

While the first set of expectations refers to the content and substance of the presentation, the latter set of expectations largely refer to design, but design and organization are important to creating an effective presentation. Students should be given examples of good slides and presentations, as well as bad ones. See the Additional Resources at the end of the article for examples. With a twenty-second limit for each slide, students should avoid using the default of bullet points. Each slide best conveys just one idea, one element, or one set of data. Students may be encouraged to use informative or humorous graphics whenever possible. A good illustration, cartoon, simple table, or well-constructed graph conveys a great deal of information that can be taken in quickly. The spoken part of the presentation should be written first, and then the student can turn to the task of designing an appropriate slide. At times, the visual aid may not be relevant and/or misused. This provides an excellent opportunity for a discussion on why the student designed that particular slide and can serve to both check understanding and move class discussion forward in other ways. Unscheduled time can be built into the presentation days to pursue discussion, or another class period can be devoted to a retrospective. I often select a few slides that I think are interesting and refer to these as a jumping-off point for review and progressive discussion.

I have used PK both for student presentations at midsemester to present paper proposals and hypotheses, and at semester’s end to showcase a term project. With a six-minute, forty-second length per presentation, I have been able to get through about ten presentations within a seventy-five-minute class session. Alternatively, students can upload recorded presentations in QuickTime video format or by using the PowerPoint narration recording function to upload to Blackboard, Dropbox, Google Drive, or other sharing sites for assessment outside of class.

Another consideration is that the presentation goes hand in hand with the paper or project that is assigned. Of course, the presentation itself can be the assignment, but PK is most effective in allowing students to reflect on a more substantive written assignment, and the process of creating the slideshow is an opportunity for them to check whether they are able to communicate their ideas to others. Students have noted that while the preparation for PK is fun and the selection of images is especially enjoyable, the construction of a presentation is hard work, especially as it reveals to them the flaws or weaknesses in their arguments, or lack of organization and clarity. They also admit that while they are nervous in delivering the preparation, the extremely short timeframe prevents them from dwelling too long on their nervousness. On occasion, an especially nervous student may need a “do-over” when she or he gets off track with the slides. Knowing that they are at the mercy of the automatic timer means that students spend much more time in preparation and rehearsal, and the benefits of this have been evident in their classroom performance.

As they construct their papers or projects, students should also think about the organization and flow of their presentations. Just as a good paper will clearly present a research puzzle, question, or claim upfront, followed by supporting evidence, discussion of alternative explanations, and a well-supported conclusion, a good presentation follows a similar logic.

Students should understand that the presentation requires intensive preparation and rehearsal. They, and you, should also understand that PK does not allow for an in-depth discussion of any particular point. It is an overview, as most presentations are. This is why it is a good supplement, not substitute, for meatier, written assignments.

A final benefit is that the discipline of preparing a PK presentation will stand students in good stead in their future professional lives. Ideally, they will be capable of entering a boardroom and not turning it into a bored room. PK, used conscientiously, can promote conciseness, precision, clarity, and organization.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

More on PechaKucha 20×20 can be found at their official site: http://www.pecha-kucha. org/.

There are many examples on YouTube if you do a search for “PechaKucha.” This one is a good training video: Pecha Kucha Training Bite, http://tinyurl.com/5w3v28.

Additional background and an interesting application are in these videos:

PechaKucha: Get to the PowerPoint in 20 Slides, http://tinyurl.com/2ze363.

Digital Inspiration, http://tinyurl.com/yjwxtgl.